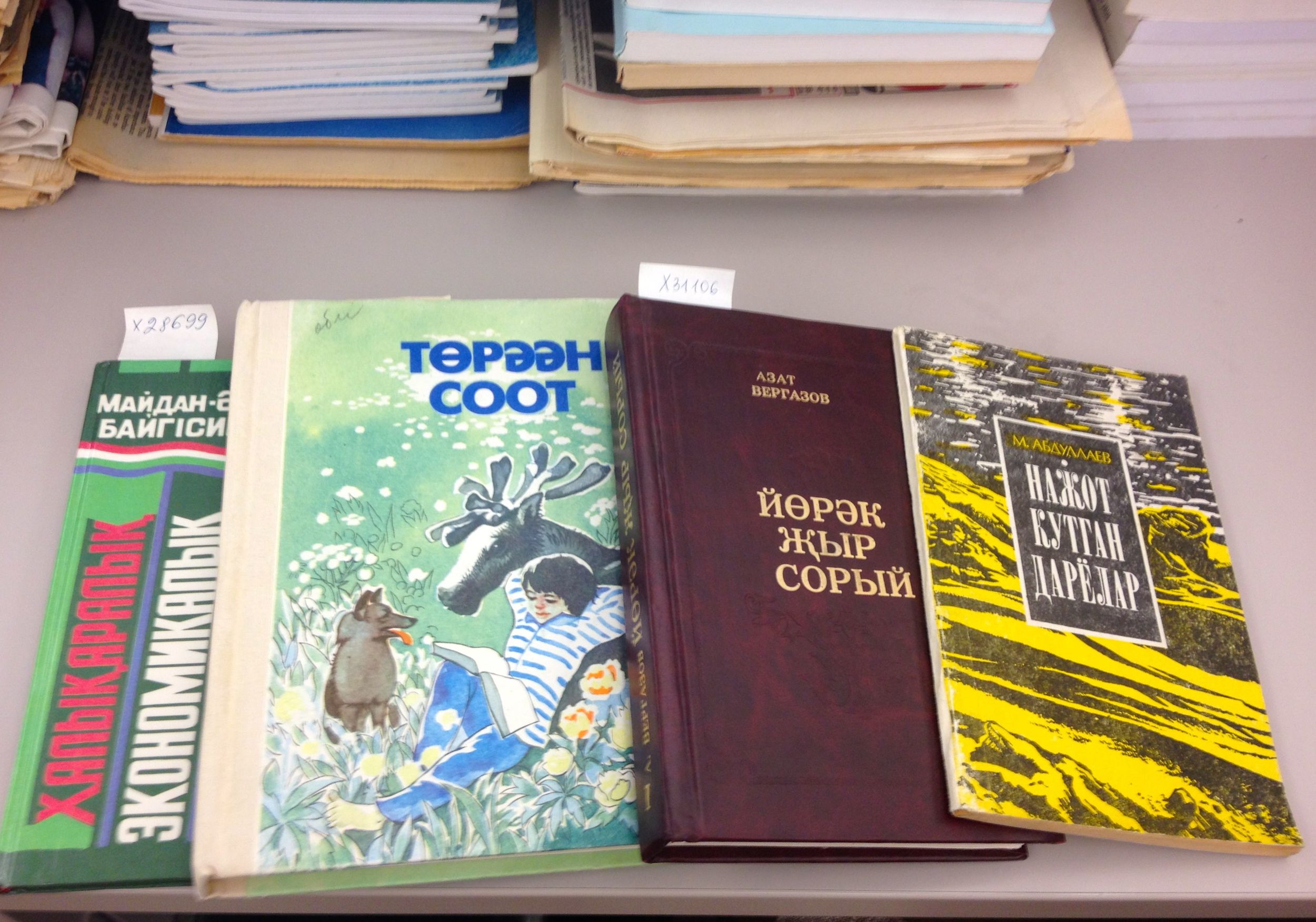

For me, the highlight of last week was finding a children’s book. It’s the book in the middle of the photo above – the one with the picture of the little boy and the reindeer. I found it while working in the library and discovered that it was written in the “Tofa” language. I had never heard of this language before, so I did some googling and discovered that the Tofalar are a Turkic people group who live in Siberia and have historically supported themselves through hunting reindeer and reindeer husbandry. The Tofa language is an endangered language and had only 731 speakers in 1989.

Pretty crazy, right? At least for a linguist nerd.

I am frequently surprised by how many cool things we have in our library. But as much as I am grateful for being at a University with huge piles of interesting books – I am more grateful to the librarians who actually make all this stuff accessible to me. Working in the library this summer, I’ve gained a new appreciation for the work that goes into making something “accessible”. Making something accessible requires a combination of organizing, and advertising, framing, developing a system and teaching others to use that system. It is definitely not enough for something awesome to exist.

So what does it look like for those of us who are not librarians to make the cool things we work with accessible to others? In my line of work, we are always encouraged to publish our papers in academic journals. I think the general idea is, the more you publish, the more likely you are to land a job. I’ve always been a little resistant to narratives that run along to lines of “do this and you’ll be sure to be super employable”, but if I spin it another way the narrative could be “If you publish, you are taking steps towards making your work accessible to a larger group of people”. That narrative I can get on board with.

But then comes the other question - who exactly do you want to make things accessible to? Just as a great idea in your head is of no use to other academics, a great idea in an academic journal is of no use to your neighbors down the street. This is where making something accessible can get really creative.

Sara Kendzior gave a talk last year at through the UIUC Anthropology Department, titled “How (and Why) to Write for the Public [as academics]”. She spent a lot of time talking about the importance of using social media – emphasizing that using mediums that others are using is one way to make your research accessible to them. In long talks with my artist friend Emma, I’ve also learned a lot the ways in which certain artists are trying to make their work more accessible by making it socially interactive. The possibilities are really endless in terms of ways to make your cool ideas and data accessible to other people.

I think the main shift though is taking on the burden of access. When we are so enamored with our work (regardless of what kind of work it is) that we think people should just come to us– then we put the burden to find, be interested in, and understand our work on them, rather than on ourselves. This kind of thinking says advertising is a dirty word and if people can’t understand us it’s because they’re not smart enough. In reality, we probably could learn a little from those who work to get their ideas noticed and we probably need to work a little harder at using less complicated explanations. Granted, this doesn’t mean that we should treat our audience like children, or that the best way to make something accessible is to explain it to death. Overall, I am simply realizing that sharing takes a certain level of humility – humility that I learn every time I rewrite a post for this blog.

And this is the last thing that I want to say about librarians that I’ve seen. They operate in humility rather than entitlement. They are always looking for more ways to make their resources more accessible to their readers. They add more information or less information based on what they think will be most useful for their patrons. They spend time making scans searchable or teaching peoples how to use their library system. They both work to make the wonderful things at the library more accessible and are constantly reevaluating what accessibility looks like. Thank you to librarians in the Slavic and East European Library that I’ve had the honor to work alongside this summer.

How do you make your ideas and your work accessible to others? What are some of the most creative solutions you’ve seen?